Why do scientists care about what kingdom an organism would belong to?

The questions "What are species?" and "How practise we identify species?" are hard to answer, and accept led to debate and disagreement amid biologists. See how consensus on answers to these questions can steer global, political, and fiscal pressures that touch conservation efforts.

Most people have a basic idea of what species are, even if they are not certain of the best way to define the word species. Quite merely, species are kinds, or types, of organisms. For example, humans all vest to one species (the scientific name of our species is Homo sapiens), and nosotros differ from other species, such as gorillas or dogs or dandelions. But defining, identifying, and distinguishing betwixt species really isn't that uncomplicated. In fact, information technology is frequently a complex and difficult process-especially in cases of new or previously unknown species. Biologists frequently disagree nearly species, and even argue over how best to define the word species. This disagreement is so well known, and and so much discussed, that information technology is sometimes referred to by biologists as the "species problem" (Hey 2001).

This article explores the idea of species, including both the meaning of the word species, and how biologists think species tin can exist identified in nature. It also examines why an understanding of species is important, both for the report of biological science and for our gild.

Why Are Species Then Confusing?

The fundamental difficulty when studying species is that, even though all species are kinds of organisms, all kinds of organisms are not species. For example, birds are a kind of organism, just birds are not a species --there are many thousands of species of birds. For scientific purposes, it is non plenty to identify a kind of organism. As a biologist yous must as well determine what level or rank of kind to assign to an organism. If you discover a new kind of organism so you must decide if information technology should be chosen a new species, or if information technology falls within an already described species. For example, the common chimpanzee species, Pan troglodytes, appears to include several slightly different kinds of chimpanzees. Each of these take been given the rank of sub-species. Alternatively, a newly discovered kind of organism might be so different from other known species that it receives non only a designation every bit a new species simply also a ranking every bit a new genus.

To help understand the confusion and uncertainty over species, let's look at the most bones idea of Darwin's theory of evolution by natural option. Darwin figured out a procedure by which species could change over time, and he believed that evolution was a slow and gradual procedure that played out over eons of time. Then if species are irresolute slowly, and if new species are formed at the slow stride of evolution, then we admittedly expect there to be cases where we struggle to decide whether two kinds of organisms should be grouped every bit separate species or equally a single species. In his book, On the Origin of Species, Darwin famously wrote, "I was much struck how entirely vague and arbitrary is the distinction between species and varieties." (Darwin 1859). In other words, Darwin did not believe that at that place was a definite betoken at which a species came into beingness. Finally, considering the large majority of species come into beingness gradually, it is not surprising that nosotros take difficulty deciding when to identify new species or what the best way to do so should be.

What Is a Species? How Do We Know a Species When We Find One?

Imagine y'all're a biologist on a research trek to look for previously undiscovered kinds of butterflies. If you detect some butterflies that seem different from those species that are already known (Effigy one), and so you are faced with two questions. The first question is "what are species?", or to put information technology some other way, "what makes a kind of butterfly an bodily species of butterfly, rather than a sub-species or a genus?" The 2d question is "how should a species exist detected?" The answer to this second question depends on the answer to the first question (i.e. "what are species?") but the ii questions are not the aforementioned.

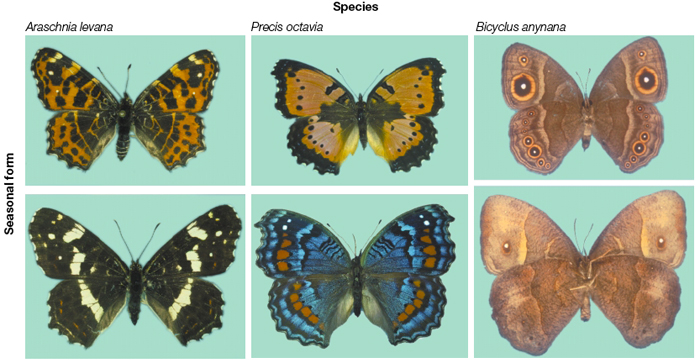

Figure ane: Variation within species

Within the same species, individual organisms can look very dissimilar. For all three species of butterflies, fly color and design varies depending on the season during which they were born. The butterflies at the top were born under unlike temperature and light atmospheric condition than the ones at the bottom.

A. levana and P. octavia photos courtesy of Fred Nijhout, Duke Academy, N Carolina, Us. B. anynana photos courtesy of Dr. Paul Brakefield. All rights reserved. ![]()

This business concern of having separate "what" and "how" questions near species is part of the confusion around species (de Queiroz 2005). In the past most biologists idea that knowing what species are (i.e., having an reply to the "what" question) was basically the same equally knowing how to detect species (i.due east., having an respond to the "how" question). The two questions are closely connected, just they are not really the same affair. For example, biologists might have a theoretical idea of what species are too equally a practical procedure for identifying species. The theoretical thought addresses the "what" question, while the practical procedure addresses the "how" question. It is possible that different scientists share the aforementioned theoretical thought about species, but really rely upon dissimilar practical procedures for identifying them. The situation is similar to what a physicist faces when trying to detect unseen particles. The physicist may know what an electron is, but that is not the aforementioned as knowing how to find an electron. The theoretical idea of the electron, when it is put into practical applications, has yielded multiple ways to detect electrons. In the aforementioned way there are multiple ways to detect species, and some may exist better than others depending on circumstances.

Two Classic Viewpoints on What Constitutes a Species

Biologists struggled with questions on species identification even before Darwin introduced his theory of evolution by natural selection. Then, when Darwin showed how species alter over time, species-related questions became even more hard. In the mid-1900s the leading evolutionary biologists, Ernst Mayr and George G. Simpson, contributed ii key ideas most the bones nature of species.

Ernst Mayr: Members of a Species Share Reproduction

In 1942 the famous biologist, Ernst Mayr claimed that what makes species dissimilar from sub-species and genera is that the organisms within a species tin can reproduce (i.e., produce fertile offspring) with ane some other, and that they cannot reproduce with organisms of other species (Mayr 1942). Mayr believed that individuals of the aforementioned species recognize each other as potential mates and are able to produce fertile offspring, but individuals of different species volition either non attempt to reproduce with 1 another, or if they try they will not produce fertile offspring. The result of this reproductive bulwark is that different species do not commutation genes with each other and therefore evolve separately from each other. Mayr was not the offset to country that this property of shared reproduction inside species (and lack of reproduction between species) is what makes species unlike from genera and sub-species. Just more than other biologists, Mayr emphasized using reproduction as the basis of species identification (see beneath); and more than about biologists before him, Mayr placed a potent emphasis on reproductive separation betwixt species.

Did Mayr get it right? Is sexual reproduction the true essence of species? One significant problem with Mayr'due south idea is that some organisms, like leaner and some eukaryotes, exercise not engage in sexual reproduction. For these organisms Mayr'southward ideas only do not apply. But kinds of non-sexual organisms practise exist, and biologists take divided them into a wide variety of different types or species, such as the thousands of species of bacteria that have been described. In these cases Mayr's idea that sexual reproduction defines species clearly is not appropriate. Simply for sexual organisms, such every bit most animals, plants, fungi and protists, Mayr's idea has been very useful.

George G. Simpson: Members of a Species Share an Evolutionary Process

Another thought was articulated past George G. Simpson. He said that something even more fundamental about species than Mayr's idea of shared reproduction is at work; that the members of a species have shared in an evolutionary process and an evolutionary history (Simpson 1951). Simpson's key idea is that a species is an evolutionary lineage that has evolved separately from other species. In other words, the organisms within a species all share in the processes of evolution. The processes of evolution, including genetic drift, migration and adaptation, cause there to be a thing, an entity made upward of organisms evolving in concert and that collectively form a species (Templeton 1989).

Chiefly, this property of evolving together does not utilise to kinds of organisms above the species level. For example, birds are not evolving all together. There are many separate species of birds, each of which is on its own evolutionary path. The same goes for mammals and plants, and indeed for whatever inclusive kind of organism that includes multiple species. One nice point about the general thought of a species as an evolving unit of measurement is that information technology fits those organisms - such as many leaner and some eukaryotes - that do not engage in sexual reproduction.

Mayr's and Simpson's Ideas Today

For the most part, biologists agree that species are fabricated upward of organisms that are evolving together. And they also concur that for sexual organisms, shared reproduction within species and the development of reproductive barriers between species, are major factors that crusade species to be. Where biologists tend to disagree is how these general theoretical ideas should translate into methods for detecting and identifying species. In other words, biologists agree that these ideas help us answer the question of what species are, just they are not in agreement nearly how much these ideas help answer the question of how to identify species.

Identifying Species with the Biological Species Concept

For Ernst Mayr the answer to the question of how species are identified too boiled down to reproduction. In other words, Mayr was using the idea of reproductive separation of species to answer both the "what" and the "how" questions almost identifying species (Mayr 1957). To Mayr, the key to identifying species is determining whether there is shared reproduction inside a population of organisms and whether there are barriers to reproduction with other organism. Mayr called this thought of defining species on the basis of reproduction the Biological Species Concept, or BSC.

Figure two: Western meadowlark and eastern meadowlark: two singled-out species

Even though they wait akin and have overlapping ranges, the western meadowlark, Sturnella magna (left), and the eastern meadowlark, Sternella neglecta (right), take distinctly different songs. As a consequence, they do non interbreed and are classified as separate species.

The BSC has been very widely discussed and debated, and many biologists call back that Mayr is essentially correct about what species are and how they should be identified. For example, while the western meadowlark and eastern Meadowlark of the U.Due south. (Figure ii) are very similar in appearance and take overlapping geographic ranges, their distinctly different songs prevent them from interbreeding. Under BSC rules they are classified as two different species. In this case, using the BSC to decide whether you have one or more one species is very straightforward. Withal, in many BSC cases, the decision is not straightforward at all. This is particularly true if yous're trying to make up one's mind whether two carve up populations in different geographic locations belong to the same species. When geographical separation is involved, the individuals in the unlike populations have no chance to reproduce with each other. If the populations cannot interact under natural weather condition you cannot know for sure if they would reproduce. Artificial conditions such as zoos and laboratories are not a valid way to make up one's mind whether individuals will reproduce in the wild, since members of a wide variety of species will reproduce with those of other species in a zoo, merely not in their natural habitat.

The Phylogenetic Species Concept Is an Alternating Approach

Because of the limitations of using the BSC to brand decisions about species, many biologists have proposed other ways to identify species. One pop approach is chosen the Phylogenetic Species Concept , or the PSC (Rosen 1979; Cracraft 1983; Donoghue 1985). There are actually several versions of the PSC, but they all concord that species can be identified on the basis of shared traits. A group of organisms that all share i or more than features pointing to a unique common antecedent, which in turn is not shared by members of other species, would meet the criterion of species nether the PSC. The traits used under the PSC are wide ranging and include color or shape, or behavior. For example, species of plants could be distinguished on the basis of the color and shape of their flowers.

Using traits under the Phylogenetic Species Concept is a very different way of identifying species than using shared reproduction nether the Biological Species Concept. Merely similar the BSC, using the PSC accurately can still be challenging. Consider a group of organisms that all appear to be in the same population (eastward.one thousand., maybe they are interbreeding with one another) and notwithstanding some individuals in that population are of a different color than the others. When we notice different distinct organismal types inside the aforementioned population, and those types are non uncommon, it is called a polymorphism . Yet nether the PSC polymorphism might exist interpreted as the presence of multiple species.

The Importance of Understanding Species

Decisions about species and uncertainty about identifying species are non just issues for scientists. Everybody needs to be able to think about and talk about kinds of organisms. A fisherman, a hunter, a birdwatcher, a gardener, or even a person in the grocery store who shops for fruits and vegetables, is depending on being able to distinguish among kinds of organisms. So too must doctors and other medical professionals be able to identify unlike kinds of parasites, including bacteria and viruses; and farmers must be able to tell the deviation between crop plants and weeds.

It is in the preservation of endangered species that many people are most likely to experience the impact of species questions. Many organisms of many kinds are affected by the societies and economies of human populations, often for the worse. For legal, ethical and economical reasons it is a big, and sometimes hard, decision to conclude that a species is endangered. This is because in the United States, a species with endangered status receives protection that ofttimes affects the lives of the people in areas where protected species alive.

Consider the case of the Due north Pacific Right Whale, which not very long agone was recognized as a distinct species based on genetic prove and the Phylogenetic Species Concept (Rosenbaum et al., 2000). The genetic data--including mitochondrial DNA sequences--indicated that the Northward Pacific Right Whale has not been exchanging genes with other populations for a very long fourth dimension. Because this whale population is so small, its new species status meant that the Endangered Species Act could exist invoked. In 2008 the species was officially listed equally endangered (Federal Annals, 2008). However, there are thought to exist only a few hundred of these whales still living and little has however been done to protect their habitat. Habitat protection has wide-ranging governmental and political repercussions, including limits on aircraft, fishing and oil-drilling activities in a role of the northern Pacific Body of water. In other words, it could be expensive to save the Due north Pacific Right Whale. Still saving the Correct Whale is important for ocean ecology, and thus for the thousands of other species that share the food web of the Pacific Bounding main with the Right Whale. Saving the Right Whale is besides important for strengthening peoples' connections to the beauty and wonder of the world's oceans and the life they contain.

Summary

Understanding species of organisms requires that nosotros accept insight into the the evolutionary processes that crusade biological variety, and that we develop practical methods for species identification. "What are species?" and "How do nosotros identify species?" are difficult questions to answer, and have lead to much argue and disagreements among biologists. One prominent fence centers on whether shared reproduction-under the Biological Species Concept-is a more than useful criterion for identifying species than shared features of organisms-under the Phylogenetic Species Concept. An understanding of what species are and how to identify them is critical, both for biologists and for the general public. Biological diversity is being lost every bit species go extinct, and it is simply by understanding species that we can shape the social, political, and financial forces that touch conservation efforts.

References and Recommended Reading

Beldade, P. & Brakefield, P. The genetics and evo-devo of butterfly fly patterns. Nature Reviews Genetics 3, 446 (2002).

Cracraft, J. Species concepts and speciation analysis. Current Ornithology ane, 159-187 (1983).

Darwin, C. On the Origin of Species by Ways of Natural Selection. Murray, London, 1859.

de Queiroz, Thousand. Ernst Mayr and the modern concept of species. PNAS 102 Suppl 1, 6600-6607 (2005).

Donoghue, 1000. J. A critique of the biological species concept and recommendations for a phylogenetic alternative. The Bryologist 88, 172-181 (1985).

Federal Register. Endangered Condition for North Pacific and Due north Atlantic Right Whales. 73 FR 12024 (2008).

Hey, J. The mind of the species problem. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 16, 326-329 (2001).

Mayr, Eastward. Systematics and the Origin of Species. Columbia University Printing, New York, 1942.

Mayr, Due east. Species concepts and definitions. Pp. 1-22 in Mayr, East., ed. The Species Prblem. AAAS, Washington, 1957.

Rosen, D. Eastward. Fishes from the uplands and intermontane basins of Republic of guatemala: revisionary studies and comparative biogeography. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 162, 267-376 (1979).

Rosenbaum, H. C. et al. World-broad genetic differentiation of Eubalaena: questioning the number of right whale species. Molecular Ecology nine, 1793-1802 (2000).

Simpson, Thousand. G. The Species Concept. Evolution 5, 285-298 (1951).

Templeton, A. R. The meaning of species and speciation: a genetic perspective. Pp. iii-27 in Otte, D. & Endler, J. A. eds. Speciation and its consequences. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA 1989.

Source: https://www.nature.com/scitable/topicpage/why-should-we-care-about-species-4277923/

0 Response to "Why do scientists care about what kingdom an organism would belong to?"

Post a Comment